[Readers] adore images that trot by like a unicorn in pyjamas -- Arthur Plotnik

As I was preparing for my annual rereading of Strunk and White's Elements of Style, I happened to listen to an episode of Writers on Writing, a podcast that included an interview with Arthur Plotnik, author of Spunk & Bite: A Writer's Guide to Punchier, More Engaging Language & Style. Plotnik was a delightful interviewee -- witty, thoughtful, enthusiastic, and highly inventive in his locutions. His reading from Spunk & Bite made me want more, so I checked the online library catalogue and found a copy at my local branch. Great, I thought. I'd been wanting to inject some freshness into my writing, and Plotnik's funny, irreverent tone caught my fancy. Perhaps I too could dress some unicorns in pyjamas.

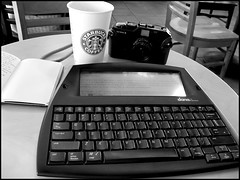

The book reads crisply as Plotnik paces the reader through energetic displays of cleverness. He has even invented his own words for metaphors that describe enormity at one scale, and the microscopic on the other: megaphors and miniphors. For someone like me who writes simply and likes his coffee plain, this was like graduating into the barista talk of Starbucks. No simple brew here -- this was the stuff of pumpkin spice lattes and iced caramel macchiatos. Strunk and White, eat my dust! For anyone whose writing needs a jolt -- cola or otherwise -- Spunk & Bite is a tonic. Oops, I think that was a mixaphor.

Nonetheless, something about the book bothered me. It made me feel inadequate and I needed to understand why. I'm not always a confident writer. Although I have confidence that I can turn out a clear, concise, and easy-flowing essay or article, I'm more essayist than poet. For me, writing is hard work -- I pick at my thoughts and words slowly. I envy those whose flights of fancy can lead them into the world of fiction or poetry or who can knock off book chapters in a single session.

When it comes to style I'm a classicist. I prefer clean, uncomplicated prose with varied sentence structure and a clear sense of direction. Although I know plenty of writer's words, as Plotnik callls them, I rarely use them. I can be witty, but I try not to overdo it. I prefer thought, rather than cleverness, to drive my prose.

The more I read Spunk & Bite, the more uncomfortable I became with it. It sounded too now, too Wired. Attitude uber alles. Exaggeration for its own sake. And more than a little bit of old-fashioned showing off. A tincture of imagery and clever writing goes a long way. I like imagery, but think writers should play small ball with it. Spunk & Bite is Barry Bonds glitter with a focus on the big swing.

Plotnik's repeated jibes at Strunk & White also began to gall. While I don't canonize the book, it's my talisman of sage writing advice. I'm capable of making up my own mind about some of its admonitions and I agree that some of them are a little dated. But the emphasis for me is on a little. Poltnik implies that its pre-Internet advice leads to dull writing in a multimedia age.

The same day I picked up Spunk & Bite from the library, I also picked up a copy of A Field Guide to Getting Lost, by Rebecca Solnit. Solnit is one of my favourite essayists. She captivates me again and again partly due to her subject matter and largely due to her style. I read the first chapter, an essay called "Open Doors". Here were the thoughts of a fine mind inviting the reader as companion as she explored new ideas about what it means to be alive. In clean, gorgeous, classical prose that would make Messrs. Strunk and White smile. I felt cleansed. Leave the cleverness to others, the prose sang to me. Get on with the journey.

It's not that I wouldn't recommend Plotnik's work to those looking to freshen up their prose. Each time I returned to Spunk & Bite, I found fresh ideas and passages to enjoy. That in itself makes the book worthwhile. But when its due date arrived, I was happy to return it to the library and reflect on its visit into my mind. It was like entertaining a lively guest full of wit, puns, repartee, and joie de vivre -- fun, but exhausting. Spunk & Bite is good as a dinner guest from time to time to keep things lively. In contrast, Strunk & White is an old friend, perhaps aging, but very dear and proven -- the kind who's welcome for long fireside chats. In the long run, nothing beats an old friendship for trust and affection.

-30-